Case Study_Monte Cecilia_FINAL

Acknowledging the milestone that CHA has reached is a privilege.

It was saddening earlier this year to learn of the passing of our inaugural chair, Neville Wilson. Neville migrated from Fiji to New Zealand in 1995 to work in the NZ public sector, and when he chaired the then CHAI council, he was working at Habitat for Humanity.

Starting a project to document the history of community housing through the window of CHA, is a demonstration of gratitude to people like Neville.

People can be too easily forgotten, and records of the mahi we collectively contribute to, are too often lost.

As vital as they are, ours is more than the history that can be gathered from annual general meetings, reports or conferences alone.

The story of CHA is a human story, drawing from all the people who have served and supported this organisation and its kaupapa over the last two decades.

Ka Mua Ka Muri is an often used whakatauki to describe the notion of ‘walking backwards into the future’ – the idea we should look to the past to inform and to inspire the future.

Kia manawanui to all the people who see CHA as their wharenui!

CEO of CHA

Deputy CEO of CHA

The milestone of our 20th anniversary is an opportunity, especially, to offer a heartfelt thank you to those who have held CHA together during these years.

Present: Amanda Kelly, David Zussman, Peter Stowers, Ruth Avery, Talavao Ngata, Wendy Marr

Past leadership: Margie Scotts, Thérèse Quinlivan, Dan Neely, David McCartney, Iris Clanachan, Scott Figenshow, Victoria Crockford

Past staff (including interns; by first name): Abby Burns, Angela Perez, Angie Cairncross, Beba McLean, Ben Lee-Harwood, Brennan Rigby, Clare Aspinall, Cushla Managh, Danae Gardner, Gill Burns, Gunda Tente, Hope Simonsen, Jane McKenzie, Janice Hill, JoAnne Carr, Jordan Kendrick, Juan Duque, Justin Latif, Katelin Livingstone, Kayden Briskie, Kaye-Maree Dunn, Lucinda McNally, Marc Slade, Moira Lawler, Natalie Jameson, Ngahuia Wright, Nikki Scoble, Rebecca Aston, Stephen Olsen, Susannah Olssen, Theo Burnard

Chairs/ Deputy Chairs/Co-Chairs: Neville Wilson, Tiopira Hape Rauna, Andrew Wilson, Riri Ellis, Faith Denny, Alan Johnson, Alison Cadman, Warren Jack, Julie Nelson, Allan Pollard, Bernie Smith, Cate Kearney, Greg Orchard, Nic Greene

Treasurers: Lisa Howard-Smith, Keith Preston, Allan Pollard, Carrie Mozena, Greg Orchard, Hope Simonsen, Cate Kearney

Council members not already mentioned – including Te Matapihi representatives (in surname order): Niko Broughton, Victoria Carroll, Gabby Clezy, Sheryl Connell, Kindra Douglas, Scott Figenshow, Kara George, Vicky George, Brad Grimmer, Fiona Hamilton, Ali Hamlin-Paenga, Arohanui Hawke, Rau Hoskins, Anthony Hughes, Anne Huriwai, Jade Kake, Patrick Kay, Moira Lawler, Elaine Lolesio, Garry Moore, Michael Noonan, Jim Palmer, Neil Porteous, Campbell Roberts, Julie Scott, Annette Sutherland, Teresa Tepania-Ashton, Peter Taylor, Craig Thomson, John Wade, Yvonne Wilson, Lisa Woolley

The approach we’ve taken to compiling a timeline of the last 20 years is intended as a conversation starter. You’ll no doubt find reminders of the rollercoaster ride our sector has been on with each successive Government – the structural changes, the policy turns, the swings and roundabouts of funding. Hopefully you’ll also see signs of the consistent directions and actions taken by CHA, with membership and partner participation.

Community Housing Aotearoa Incorporated (CHAI) formed in November

5th Labour Government Coalition)

Helen Clark PM (1999–2008)

Steve Maharey in place as Minister of Housing (2003–05) Department of Building and Housing established Same year as the introduction of Working for Families, New Zealand’s key income assistance programme for families.

Co-ordinator: Margie Scotts

CHAI holds its first AGM and Conference in Auckland

New Zealand Housing Strategy launched in May Chris Carter becomes next Minister of Housing.

National Director: Thérèse Quinlivan

CHAI’s Māori caucus holds a hui in Rotorua

Budget 2006 provides $16.4M top-up for council and community based housing.

CHAI publishes the first edition of its "Good Practice Guide"

Maryan Street replaces Chris Carter as Minister of Housing.

Pathways out of Homelessness Programme launched.

CHAI rebranded as CHA

2008 CHA Conference in Wellington: Building the Future – Housing Our Communities.

Pacific Island Housing Forums launched.

5th National Government (Minority)

John Key PM (2008–16)

Bill English PM (2016–17)

Phil Heatley starts as Minister of Housing (holds the portfolio until January 2013).

CHA issues media release supporting unified approach to papakāinga housing in Northland

Budget 2009 delivers $20M in capital funding for HNZ’s Housing Innovation Fund.

Executive Officer: David McCartney

First National Māori Housing Conference is held in Rotorua

Housing Shareholder’s Advisory Group releases

its Home and Housed report.

Repeal of the Affordable Housing: Enabling Territorial Authorities Act.

2011 CHA Conference in Auckland: Doorways to Community Housing

Establishment of Te Matapihi He Tirohanga Mo Te Iwi Trust.

The Centre for Housing Research Aotearoa NZ (CHRANZ) closes.

Implementation of the Social Housing Reform Programme begins.

Criteria released by the new Social Housing Unit for the $140M Social Housing Fund.

Acting EO: Iris Clanachan

CHA returns cheque to MBIE over contract restrictions

2012.

National Māori Housing Conference held in the Bay of Islands.

Department of Building and Housing integrated into MBIE.

Chief Executive Officer: Scott Figenshow

CHA Constitution amended to replace Māori caucus with a Te Matapihi rep.

MOU in place with MBIE Housing Accords and Special Housing Areas.

Act 2013 passed.

2014 CHA IMPACT Conference in Nelson: Making

Community Housing Happen.

CHA delivers CHO Sector Survey report to the Treasury Establishment Unit.

Community Housing Regulatory Authority established, and registered CHPs become eligible for IRRS.

Paula Bennett becomes first Minister for Social Housing.

2015 CHA IMPACT Conference in Wellington: Connecting the Dots on Community Housing.

CHA produces A Safe Pair of Hands: A Snapshot of the Community Housing Sector.

CHA releases draft of Our Place towards a coordinated housing strategy and human rights framework.

CHA subsidiary New Zealand Housing Bonds Ltd formed with MBIE and Auckland Council Support.

Introduction of the Social Housing Reform (Transaction Mandate) Bill MSD receives a baseline valuation of the social housing system.

CHA makes a submission to the cross-party inquiry into homelessness.

Amy Adams replaces Paula Bennett as Minister for Social Housing.

Crown signs contracts with Accessible Properties for stock sale of Tauranga portfolio.

2017 CHA IMPACT Conference in Wellington: Building Our Place.

CHA subsidiary Community Housing Solutions Ltd formed.

Penina Health Trust becomes the first Pacific organisation to gain registration as a CHP.

CHA participates in Auckland Housing Summit.

6th Labour Government (Coalition)

Jacinda Ardern PM (2017–23)

Chris Hipkins PM (2023)

Labour ends stock transfers A $16.4M expansion of the Housing First programme.

Phil Twyford first Minister for Housing and Urban Development.

CHA and Beacon Pathway partner on Housing Matters: Delivering Good Medium Density event.

MSD publishes the Public Housing Plan.

Establishment of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development.

KiwiBuy campaign launched.

Peter McKenzie Project (PMP) funding announced.

2019 CHA Shift Aotearoa Conference in Wellington: New Knowledge for

Housing Action.

Megan Woods appointed as Minister of Housing HNZ replaced by Kāinga Ora Homes and Communities.

KiwiBuild reset, $400M Progressive Home Ownership fund.

CHA supports production of the We Believe video by the Auckland Community Housing Providers Network.

CHA and Human Rights Commission partner on visit by UN Special Rapporteur Leilani Farha.

Homelessness Action Plan published.

Progressive Home Ownership Scheme launched.

ACC makes $50M investment in joint venture with CORT.

Chief Executive Officer: Victoria Crockford

2021 CHA Shift Aotearoa Conference (online).

Launch of MAIHI Ka Ora – the National Māori Housing Strategy.

Whai Kāinga, Whai Oranga funding for Māori Housing.

HRC releases its guidelines on the right to a decent home.

Government Policy Statement on Housing and Urban development.

Chief Executive Officer: Victoria Crockford / Paul Gilberd

CHA hires Pacific Relationship Manager and Policy Advisor.

CHA podcast Right At Home commences.

Budget 2022 includes Affordable Housing Fund of $350M.

2023 CHA Conference: Unlocking Local in Ōtautahi Christchurch.

Stage One report of the Wai 2750 – Housing Policy and Services Kaupapa Inquiry.

HRC releases the final report of its two-year Housing Inquiry.

6th National Government (Coalition)

Christopher Luxon PM (2023–)

2024 CHA Conference: Growing Together held in Auckland.

Independent CommunityHousing Funding Agency launched.

New Minister of Housing Chris Bishop, Associate Minister Tama Potaka.

Kāinga Ora review delivered in May.

2024 Budget makes cuts and reductions as well as projecting $140M for 1500 new social housing places for 2025–27.

Click here for PDF copy (V1a; 5/12/2024)

If you see errors in this timeline, have additions to suggest or any other responses to make, please let Wendy Marr, CHA Communications Manager know – [email protected]

A fuller chronology is also being compiled, to accompany a bibliography of relevant research sources and publications.

The journey towards CHA began in 2003 when funding was drawn from the Housing Innovation Fund for establishment of just such as organisation.

A year later, after a tentative year of setting its operational foundations, the first AGM of Community Housing Aotearoa Incorporated (CHAI) was held on 5 November 2005 at the Waipuna Hotel and Conference Centre at Mt Wellington, Auckland.

In its ‘settling in’ period CHAI’s Council functioned in both management and governance roles. In this period CHAI suffered a sad loss when inaugural treasurer Rod Gordon passed away.

The inaugural national coordinator, Margie Scotts, was appointed in April 2005 with a focus on obtaining funding, transitioning from an interim management structure and finding office space in Wellington to share with Wellington Housing Trust.

Margie’s report for the first AGM held high hopes that CHAI would be accelerating its development and would, in short order, play an instrumental part in pursuit of the ambitious goal of putting the “need and value of good quality housing stocks that communities own, manager or facilitate access to … indisputably on the political and social map”.

The following year acting chair Lisa Howard-Smith drew attention to how easy it was “to forget that those overseas peak bodies CHAI is striving to emulate have been around for many more years”, noting that the Australian counterpart CHFA was established in 1996 and “our English equivalent in the 70s”.

In 2006 Thérèse Quinlivan took up the role of National Director at CHAI, with Margie Scotts moving on to a role at CRESA and temporary bridging provided by Libby Clements.

In the 2007/08 annual report Thérèse declared that a re-launched logo and shortening of CHAI to CHA, provided “a feeling of new beginnings and growth”. Comment was made on the adjusted branding that “whilst ‘CHAI’ was the subject of many tea jokes it lacked recognition and authority”.

Work was being initiated on a national community housing strategy and connections were made with the Australasian Housing Institute and Swinburne University to explore options for delivering housing courses. A training needs assessment identified the most urgent needs as gaining more information on a wide range of housing models and around financial issues.

By 2009 Dan Neely – the extremely able 2ic to Thérèse Quinlivan – had been filling the director role vacated by Thérèse. In this period too the Māori Caucus received a grant from Te Puni Kokiri to enable CHA to recruit a National Māori Development Worker, a position to which Kaye-Maree Dunn was appointed.

Fast forwarding to 2011 Alan Johnson was Council chair and new executive officer, David McCartney, was the only full-time staff member.

This was the year that Andrew Wilson stepped down from the CHA board, having served three consecutive terms as an elected council member.

His six years of service and taking up of the Chair and Treasurer roles during those years, deservedly earnt much praise for his “quiet patience and board competence” during challenging times. It was recorded that his commitment to CHA “has been nothing short of immense”.

Alan expressed concern that a heavier concentration of CHA’s operations around delivery of services to Government, could constrain its ability to speak out “if needs be, about the inadequacy of Government housing programmes or … for the homeless and the poorly housed”.

He urged the community housing sector to “reflect in more depth on the future of CHA”, including a weighing up of the extent to which wider commitments to “the best principles of community-based housing constitutes a ‘movement’”.

Through his executive officer’s report that year David McCartney provided an update on the early days of the Social Housing Unit (SHU) and that regional forums being held by the SHU – under Michael Pead’s leadership – had affirmed support for an increased role for CHA. While welcoming the Social Housing Fund’s available quantum of $37.35 million, David didn’t hesitate to add “it is still a drop in the bucket”.

CHA reached an inflection of leadership as it neared the milestone of 10 years in operation. After a term of almost three years, the rakau passed temporarily from David McCartney to Iris Clanachan, and then to a former council member, Scott Figenshow – previously a driving force at the Queenstown Lakes Community Housing Trust (QLCHT) formed by the Queenstown Lakes District Council in 2007.

By 2015 the securing by CHA of another three-year funding agreement with Government heralded what the annual report of 2014-15 called a new phase of “substantially stronger financial ground”.

The dedicated work that went into the “living document” presented by the ‘Our Place’ strategy set a new wayfinder for addressing communities’ needs.

CEO Scott Figenshow noted “it’s a big task but thankfully we are continuing to build strong relationships – across Government, with the commercial sector, with the community sector, with our constitutional partner Te Matapihi, and, of course, with you, our members”.

Special mention was made of four partners – the NZ Council of Christian Social Services, the NZ Council for Infrastructure Development, Prefab NZ and the Centre for Research, Evaluation and Social Assessment (CRESA) – as contributors to knowledge, expertise, evidence and the development of “common views”.

Scott’s message to members during this phase of CHA is worth repeating:

“Many of you have a depth of experience and length of memory that holds the answer to many of the most vexing challenges. We’d like to think that by channelling your voices we add value to the often short-term nature of some government decisions, proving the point that what is needed most is long-term, sustainable housing policy”.

In a contribution to CHA’s 2015 annual report Peter Jeffries, chief executive of founding CHA member CORT, pushed back on stereotypical attitudes towards community housing providers as lacking business skills or professionalism. He asserted ‘business and charity’ as the co-drivers of providers, made explicitly obvious by their ample ability to reinvest surpluses (profits) back into high standard, sustainable housing.

In 2016 Scott delivered an appreciation of colleagues throughout the housing system for engaging in the “hard conversations”, set against an honest recognition to how vexing the impression of slow progress can be and the “never ending challenges”.

His was a consistent drumbeat in pursuit of momentum, “being tested to up our game” and to be at the forefront of the delivery of housing even when funding models were failing to make the provision of additional affordable housing feasible.

Scott: “We need to grow, to have an appetite for scale, and to challenge each other to deliver more homes”.

Messages of frustration from the CHA board were loud and clear, such as frustration at “sector capacity being chewed up by an expensive procurement approach that doesn’t always meet peoples’ housing needs”. Along with frustration at “resources being expended to compete for funding rather than deliver new homes”. Deferring to a market response to housing demand for vulnerable families and individuals hadn’t and wouldn’t cut it.

By 2018 another political cycle and change of Government was kicking in. It was, co-chairs Julie Nelson and Allan Pollard concurred, a year “when we are at last witnessing broad acceptance of key messages and solutions that you, our members and sector leaders, have long promoted”.

Hints of an imminent golden era were palpable. The need to invest in both affordable assisted rental housing and shared ownership had reached a “being considered” threshold. Meanwhile acceptance of the housing affordability continuum was occurring across both central and local government, and levels of support and acceptance for both Housing First and emergency housing was “unprecedented”.

The sector’s general reputation for making a difference via shared focus and purpose was finally gaining a rising profile and was “poised for greater impact”. If it had been a musical it was near to a sounding out of these lyrical couplets from hit song Acquarius (Fifth Dimension, 1969):

Harmony and understanding – Sympathy and trust abounding

No more falsehoods or derisions – Golden living dreams of visions

Julie and Allan made an emboldened call for maximum support “to increase both our presence and (to) be more effective in both the media and across government”.

To that end staff were given a clear directive to seize the day by being yet “more edgy and assertive”. CEO Scott Figenshow picked up the wero, equating the directive as an encouragement to take “an activist approach for our message to get across”.

Hope was being drawn from the new Government’s well-aligned focus on well-being, coinciding with a time of CHA taking a heightened focus on a human rights approach to housing as being “at the crux of what we do as a sector” and a push for parallel legislative change.

The board was also listening to member feedback that CHA focus on “doing fewer things, but doing them better”.

And then came COVID-19. The 2020 chair’s report from Bernie Smith, remarked how “in a matter of days we all were reminded just how important a home is, as the place to shelter from the storm of a global pandemic”.

Including COVID responses it was, typically, a year of rapid changes.

Another new chapter was being anticipated off the back of confirmation from the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development that both CHA and Te Matapihi would receive equivalent funding and had been charged with delivering a joint work programme of Homeless Sector support services. A four-year term for the new contracts provided greater certainty of revenue across a longer duration that at any time before.

Peter McKenzie Project funding for Shift Aotearoa and its focus on systems settings for reduction of family and child poverty dawned as another significant event for Community Housing Aotearoa, representing a five-year commitment and the single largest non-governmental contribution received by CHA.

Activity to highlight the work of CHA members through increased communications and the development of case studies and videos and podcasts was on the increase.

One further year into operating under disruptive pandemic conditions, it was observed that the emergency .had made the apparent need for long-term solutions to housing inequity “ever more glaring”.

Looking back it’s interesting that the annual report for 2020-21 went so far as to say that the pandemic could “either become the catalyst for taking decisive action to enable affordable, healthy homes for all, or it can serve as the moment where existing inequalities are cemented for generations” – adding “our sector has a strong role to play in advocating for it to be the former”.

Scott Figenshow’s influential eight-year tenure as CHA’s chief executive drew to a close during COVID times, when he made a return to the USA. He could look back on having lifted CHA’s performance year-on-year, growing it from less than two full time staff up to a thriving team of eight.

Co-chairs Bernie Smith and Cate Kearney highlighted Scott’s ability to build relationships within housing and across other sectors as a pivotal reason for “the leadership that CHA is recognised for within the NGO sector”.

Equally long-serving deputy CE Chris Glaudel kept the CHA ship steady during an appointment and induction process that saw Victoria Crockford step into the chief executive role at CHA in August 2021, bringing with her a helpful background in communications and government relations .

Vic’s immediate perspective was that of entering an organisation confronting two crises: COVID and housing. And her immediate focus was on ensuring a “strong, cohesive voice” for CHA and its mahi as a trusted advisor to governments and decision-makers.

The enduring tail of COVID conjoined with the pressures of inflation and supply constraints contributed to the complexities for housing. On the plus side the number of net public housing homes provided under the current Public Housing Plan since 2018 was a healthy 6,000 from Community Housing Providers out of an approximate total of 9,000.

Coming into another election year co-chairs Greg Orchard and Cat Kearney clearly knew that occupying the minds of policymakers and political leaders on the need for sustainable, flexibly applied funding would be key.

Their 2022 report noted that amongst RMA reforms and looming local government elections it was noticeable that a strategic focus on inclusionary housing by CHA had showcased a level of expertise held within the community housing sector that was beginning to be sought out by planners and politicians alike.

The highlights of delivering against the 2021-22 programme included the following: bringing on a Pacific team as part of our work on Fale mo Aiga; a strong contribution to the development of the implementation plan for the Government Policy Statement on Housing and Urban Development; development of a sector pipeline software tool; benchmarking with Strategic Pay; launching Ngā Puna Kōrero with Te Matapihi; and sixteen submissions to local and central government.

The impact of severe weather events in 2023 drew co-chairs Cate Kearney and Nic Greene to comment that the housing crisis in some regions of New Zealand had “become more like a humanitarian crisis”.

On the one hand Government efforts to turn the tide on the decline of new social housing supply were commended, while on the other it was pointed out that more than 25,000 households remained on the waiting list.

2023 saw the arrival of new chief executive Paul Gilberd, formerly a general manager at Community Finance and the Housing Foundation. It also saw the first national conference in several years, hosted in the Christchurch Town Hall.

On day one of the event the collective number of years of directly relevant work experience in the room was counted. The number topped 5,600 years – a realisation and reflection of an unmatchable collective and institutional memory of the housing system.

In conjunction with CHA’s Our Place and 10-year strategy, a suite of “focus areas” had consistently continued to carry CHA through to its 20th anniversary:

One way to conduct a search for significant or ‘big picture’ moments in the historical contexts for the housing situation in Aotearoa NZ, is to turn the dial back on the historical timeline.

The most common, some might say obsessive, ‘dialling back’ is to the iconic, even mythical dawning of the State House. From the first State House opening in Miramar, Wellington, on 18 September 1937 the public and social housing landscape of New Zealand has come to be defined by the State House – as if set in concrete.

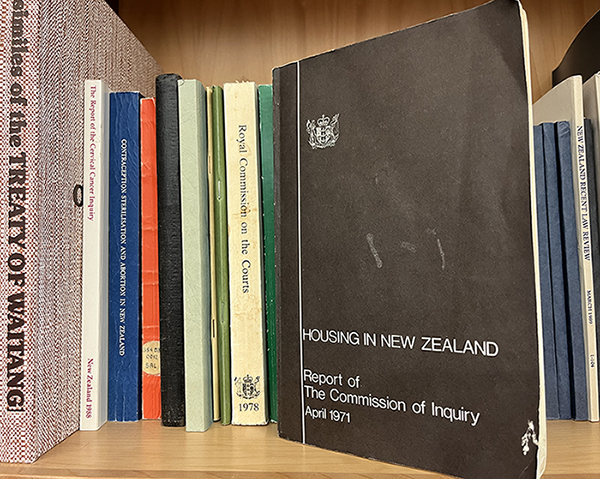

There have been many subsequent periods when the necessity of re-setting the fundamentals of housing sent wake-up calls to our political leaders and wider society. The period from 1971-1988 is something that might be called a ‘missing middle’.

A notable milestone of that period was, first of all, the report of the Commission of Inquiry into Housing in New Zealand. The Inquiry, tabled in Parliament in April 1971, occurred under a National government led by Sir Keith Holyoake and was chaired by prominent lawyer Robin Cooke (later Lord Cooke of Thorndon).

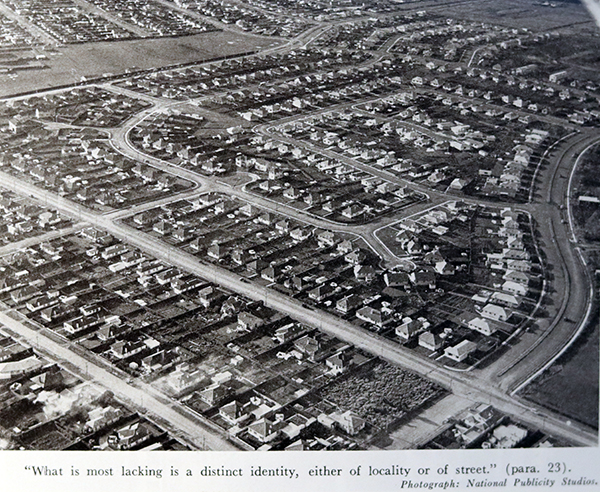

It was an inquiry precipitated by a recession-related decrease in new building activity, a rise in interest rates and rentals, and a decrease in affordability of housing. Another issue raised at the time was the inadequate planning of new suburbs, especially the provision of houses without adequate community facilities.

Some 89 organisations gave public evidence to the inquiry, but very few were from ‘civil society’ save the Christchurch Aged Peoples’ Welfare Council, Cook Islands (N.Z.) Society, NZ Association of Social Workers, NZ Māori Council, the Public Service Association, NZ University Students’ Association and Plunket Society.

Fascinating as it might be to flesh out all of the 112 recommendations made by such a long-ago inquiry, this isn’t the place to do that. Suffice to say many of them were written as detailed instructions, many make reference to the need for a national housing authority, and that many of the bigger ticket recommendations don’t sound at all unfamiliar.

Recommendations of all kinds. Recommendations like applying the principle that rents should be related to the income of the tenant.

Or directing State agencies to expand their activities in developing land for housing rather than in house-building programmes. Or that legislation regarding substandard housing be revised and consolidated. Or that district planning schemes include provision for comprehensive residential development areas in which rules governing the development of single sites will not apply. Or that in future developments the minimum ratio of public open space aimed at should be 10 acres per thousand of population density to be created. Or that the building industry give increased emphasis to the building of town houses and terraced houses in relatively central urban areas.

Suffice also to say that terms relating to housing continuums, inclusionary housing or security of tenure did not appear in the index. Prominence was still attached to the reasonably extensive housing functions of local authorities. This was more than half a century ago after all.

An astute retrospective summary of the inquiry report by historian Ben Schrader was that it “was a wake-up call intended to motivate the government to ditch its somnolent approach to state housing design and fashion a more lively vision”.

Seven years, and one Labour government later, new design policies had been gaining traction as showcased when Prime Minister Robert Muldoon opened the 100,000th state house in Broomfield – a half-state, half-private suburb out beyond Christchurch’s Riccarton racecourse (see p.124 of We Call It Home).

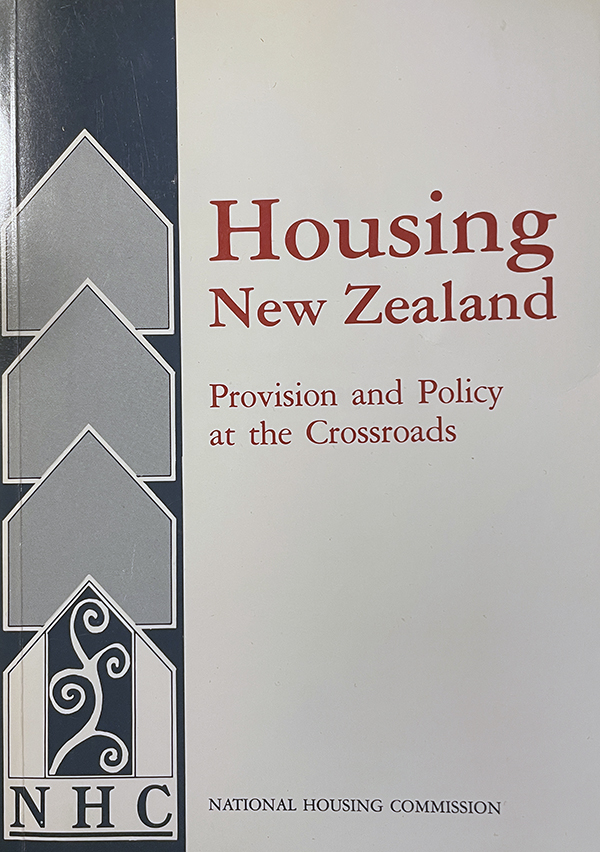

Subsequent to the inquiry a National Housing Authority with planning and executive powers was never implemented. Instead, the National Housing Commission, an independent statutory body with advisory powers only was set up, apparently over protests from the National Party Opposition who felt the Commission of Inquiry’s main recommendation had been ‘watered down’.

A view was held that the Labour Government of the time wanted to keep control of, and accountability for, housing provision firmly in its own hands and that the transfer of any executive authority to a Commission risked an abdication of its own responsibility for housing.

The National Housing Commission (NHC) first met in April 1974. Its powers extended to investigating, commenting and advising upon all matters relating to the provision of dwellings in New Zealand, with its last Five-yearly Report appearing the same year it was disestablished, 14 years later, on 31 March 1988.

In that last report comfort was taken that unlike many other nations “New Zealand does not have the huge, insoluble problems of homelessness and substandard housing”. A definite ‘buffer’ had proven to be what was described as “the legacy of our forebears in providing a relatively adequate housing stock”.

Be that as it may have been, the following clarification was added: “While this may console us as a nation, that is no consolation for people who today, in both urban and rural New Zealand society, are living in concrete bunkers, or camping grounds, or under corrugated iron sheets, or in temporary, hopelessly overcrowded conditions with long-suffering relatives.

“It does not assuage the misery of the supposedly more fortunate families in South Auckland who must live in emergency accommodation, four or five to a room, for nine months while they wait for state rented accommodation to become available. It brings no message of hope to the many families, who for official purposes may be ‘housed’, but who are paying high rentals to private landlords for small, one- or two-bedroom flats; flats where they are destined to live throughout the years of parenting, and which the previous generation would scarcely have tolerated beyond the early years of marriage.”

Looking back retrospectively to its first Five-Yearly Report of 1978 it became apparent that the “pace and scale of adjustment” that lay ahead couldn’t be foreseen. It was noted that the nature of housing need and housing provision had changed markedly between 1974 to 1988.

A central concern was the “unevenness of housing provision” with a comment that successive governments’ attempts to respond to the challenge had “partially failed in that serious housing need exists today … concentrated in particular regions and social groups”.

Several issues were regarded as longstanding. As well as the fragmented approaches to housing provision and management these included affordability, the plight of “minority groups such as single people and solo parents” and a need for greater variety in housing types and improved energy efficiency.

Eleven important ‘new issues’ were listed that had not been “perceived as central at the Commission’s inception”. These included discrimination affecting housing access, a specific crisis in Māori rural housing, the increase in housing needs accompanying deinstitutionalisation, unmet women’s housing needs, impacts of unemployment, an acceleration of regional differences and a move towards “targeting as against universality” in housing assistance.

The increased emergency needs encountered by voluntary agencies and lack of a statutory obligation to house the homeless featured as issues raised by the Commission, along with the “relative roles of state, private and voluntary sectors”. Devolution of control of resources to iwi and other community groups was there too.

There was a concern that delivery of further housing was being stalled by an escalation of land and building costs and insufficient state financial assistance.

Presbyterian Social Services, Anglican and Catholic Social Services, the Salvation Army and Wesley Social Services were cited as examples of organisations that were being stymied. Early initiatives of the 1980s being taken by the Wellington Housing Trust and Manukau Housing Scheme received praise.

Sustained arguments were put by the Commission that any planning horizon of less than 4-5 years for housing provision was insufficient and that planning for housing needs “must be assessed at a regional, local, or even a neighbourhood level”.

In its final report the Commission stood by its 1978 recommendation for the development of a national housing strategy, with regional components, directed at medium-term planning and bringing together all the parties involved in housing provision and consumption.

Commission members were disappointed that so little progress had been made towards the goal of developing a national housing strategy. There was a concern that without such a “vital prerequisite” New Zealand could find itself being pushed towards “a housing crisis comparable with those in the Northern Hemisphere”.

The demise of the Commission came with a caution from Ewing Robertson, the Commission Chair, that its provision of housing advice to Ministers of Housing had filled a necessary role and without an adequate substitute “the quality of housing advice they receive will suffer”.

Elsewhere in the report it was confidently asserted that without the Commission, the information base available and public awareness of housing issues would undoubtedly have been less.

Five major areas identified for immediate attention in the Commission’s final Five-Yearly Report make for interesting reading – more than a generation later. Calls for action were made to address:

From the distant heights of 2024 it’s a shortlist that speaks both to the issues of a former decade, and yet also a worryingly stubborn stasis.

The words written by the National Housing Commission in 1988 still hold:

“On how a nation deals with those of its members who are the most disadvantaged, in providing for their housing and welfare, depends the moral, if not (in the short run) the material, well-being of any society”.